Despite being relatively nutrient-dense and a good source of soluble fiber and resistant starch, legumes are not considered a part of the Paleo diet due to their content of a type of lectins called agglutinins as well as phytates, saponins and protease inhibitors (see Why Grains Are Bad–Part 1, Lectins and the Gut, Are all lectins bad? (and what are lectins, anyway?), How Do Grains, Legumes, and Dairy Cause a Leaky Gut? Resistant Starch: It’s Not All Sunshine and Roses) Long story short, the anti-nutrients in legumes damage the gut and aggravate a number of health conditions, including autoimmune diseases.

But, there’s still a gray zone when it comes to edible-podded vegetables like green beans (also called string beans or snap beans) and fresh peas (including sugar snap peas and snow peas). Technically speaking, these foods are definitely legumes, meaning they belong to class of vegetables from the  Fabaceae family that produce long seedpods. That makes green beans and peas related to foods like kidney beans, black beans, garbanzo beans, soybeans, adzuki beans, lima beans, pinto beans, mung beans, black beans, and even peanuts (yep, they’re not really a nut!). For those who choose paint Paleo with a very broad brush, a legume is a legume is a legume—the source of much controversy and internet hulking out whenever a blogger who identifies themselves as following the Paleo diet shares a recipe that includes green beans or peas.

Fabaceae family that produce long seedpods. That makes green beans and peas related to foods like kidney beans, black beans, garbanzo beans, soybeans, adzuki beans, lima beans, pinto beans, mung beans, black beans, and even peanuts (yep, they’re not really a nut!). For those who choose paint Paleo with a very broad brush, a legume is a legume is a legume—the source of much controversy and internet hulking out whenever a blogger who identifies themselves as following the Paleo diet shares a recipe that includes green beans or peas.

However, edible-podded legumes have a few major differences that make them an important exception to the no-legume rule! Unlike other legumes, which are harvested after their seeds (called pulses) have matured and dried, we eat green beans and fresh peas when the pods are still soft and immature. One result of this involves phytic acid or phytate, the main storage form of phosphorus in plants. Phytic acid binds to minerals and reduces their bioavailability to us (hence why it’s often called an anti-nutrient), and tends to be very high in grains, nuts, and legumes. But, studies of different legume varieties show that phytate levels increase as legumes get older and harder, so edible-podded legumes are naturally going to be lower in phytates due to their earlier stage of maturity. And, the data we have on actual phytate levels in legumes confirms that green beans and fresh peas are at the very bottom end of the spectrum! For example, one study found that 15 Polish pea varieties had phytate levels ranging from 0.006 to 0.013 grams per 100g of dry weight, which is between 80 and 370 times less than the phytate content of soybeans!

Likewise, compared to hard, dry legumes, fresh peas and green beans have lower levels of a sub-class of lectins called agglutinins (see Why Grains Are Bad–Part 1, Lectins and the Gut). Grains and legumes contain high concentrations of lectins as part of the plants’ natural defense system. And because of the negative impact on gut and immune health, it’s a good idea to avoid ingesting high concentrations of these specific proteins (since they’re not broken down in the normal digestive process, can damage or kill cells lining our intestines and cause leaky gut, act as immune stimulators, and in some cases cause acute toxicity!).

For example, kidney beans contain a high level of a very toxic and immunogenic agglutinin called phytohaemagglutinin (sometimes called kidney bean lectin). Phytohaemagglutinin is also found to a lesser extent in cannellini beans, common beans, and broad beans, such as fava beans. As few as five raw kidney beans can cause extreme gastrointestinal distress, with symptoms like those of food poisoning (not that anyone would want to eat raw kidney beans). While soaking and then cooking beans for at least 30 minutes greatly reduces the activity of phytohaemagglutinin, it does not get rid of it completely, especially when cooked at lower temperatures, such as in a slow cooker. Phytohaemagglutinin can cross the gut barrier, increase intestinal permeability, and stimulate the immune system. In fact, phytohaemagglutinin is easily detected in the bloodstream after consumption. It has also been shown to cause extensive overgrowth of Escherichia coli, or E. coli, in the small intestine (some E. coli is normal, but it is a common culprit in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth).

For example, kidney beans contain a high level of a very toxic and immunogenic agglutinin called phytohaemagglutinin (sometimes called kidney bean lectin). Phytohaemagglutinin is also found to a lesser extent in cannellini beans, common beans, and broad beans, such as fava beans. As few as five raw kidney beans can cause extreme gastrointestinal distress, with symptoms like those of food poisoning (not that anyone would want to eat raw kidney beans). While soaking and then cooking beans for at least 30 minutes greatly reduces the activity of phytohaemagglutinin, it does not get rid of it completely, especially when cooked at lower temperatures, such as in a slow cooker. Phytohaemagglutinin can cross the gut barrier, increase intestinal permeability, and stimulate the immune system. In fact, phytohaemagglutinin is easily detected in the bloodstream after consumption. It has also been shown to cause extensive overgrowth of Escherichia coli, or E. coli, in the small intestine (some E. coli is normal, but it is a common culprit in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth).

Other legume agglutinins, like peanut agglutinin (PNA, or peanut lectin), also enter the bloodstream quickly after being consumed, implying significant effects on intestinal permeability. Agglutinins from nettle (typically consumed only cooked) increase intestinal permeability.  Soybean agglutinin (soybean lectin) and concanavalin (an agglutinin in jack beans, which are often used in animal feeds) have been shown to increase epithelial permeability much as wheat germ agglutinin does. Concanavalin stimulates cytotoxic T cells and inflammatory cells from the innate immune system and is being investigated as a drug for chemotherapy (because chemotherapy drugs are more toxic to cancer cells than they are to normal cells, which seems to be the case with concanavalin). Soybean agglutinin is known to bind to and activate dendritic cells and stimulate proliferation of T cells. In fact, soybean agglutinin so efficiently targets and stimulates the immune system that it is being studied for use in vaccines to improve immunization.

Soybean agglutinin (soybean lectin) and concanavalin (an agglutinin in jack beans, which are often used in animal feeds) have been shown to increase epithelial permeability much as wheat germ agglutinin does. Concanavalin stimulates cytotoxic T cells and inflammatory cells from the innate immune system and is being investigated as a drug for chemotherapy (because chemotherapy drugs are more toxic to cancer cells than they are to normal cells, which seems to be the case with concanavalin). Soybean agglutinin is known to bind to and activate dendritic cells and stimulate proliferation of T cells. In fact, soybean agglutinin so efficiently targets and stimulates the immune system that it is being studied for use in vaccines to improve immunization.

But, it turns out that legume lectins are not a good reason to totally avoid green beans and fresh peas! Because of how they’ve been bred and their relatively early harvesting stage, edible-podded peas and green beans have low enough levels of phytohaemagglutin and other lectins to be safe even in their raw state. And, the lectins they do contain are relatively instable, which means they can easily be deactivated through cooking.

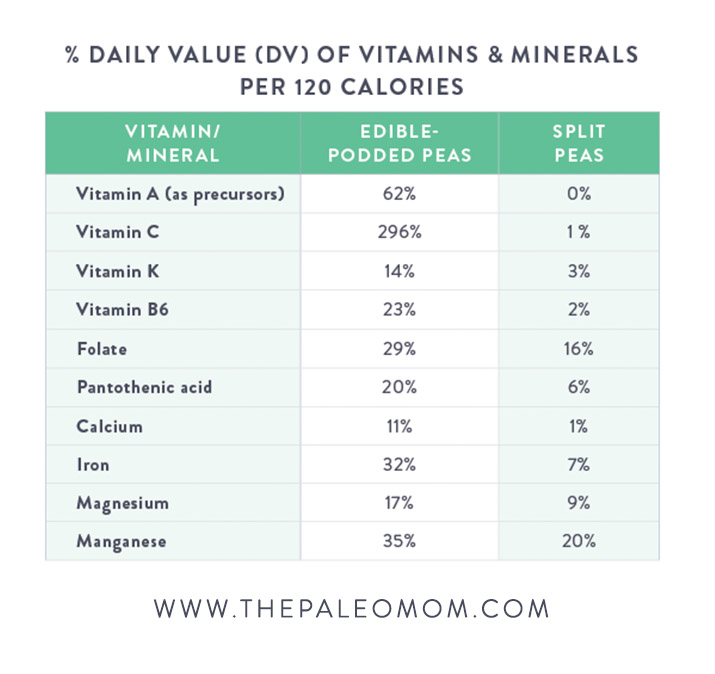

On top of that, when we eat green beans or fresh peas, we’re not just eating the plant’s seeds like we do with other legumes: we’re also consuming the pod itself, which doesn’t contain the same kinds of lectins (or same high level of phytates) that legume seeds do. In fact, the nutritional profile of green beans and fresh peas is much more similar to non-starchy veggies than it is to other legumes (including a low calorie density and high content of vitamin C and vitamin A precursors). For example, if we compare edible-podded peas (which include both the pod and the peas inside!) with mature split peas (which include only the seeds inside the pod), we can see that edible-podded peas have a higher concentration of micronutrients than mature peas. Per 120 calories of food (raw snap peas and snow peas versus cooked split peas):

So, what’s the verdict? In terms of phytate levels, lectins, and overall nutrition, edible-podded legumes don’t have that much in common with the hard, mature beans that typically come to mind when we hear the word “legume.” And while the small amounts of agglutinins may be a concern for those with autoimmune disease following the autoimmune protocol, the arguments for excluding these foods from a more standard Paleo diet fall short. If we see green beans at the farmers market, are lucky enough to have sugar snap peas growing in the garden, or just want a tasty addition to our veggie menu, edible-podded legumes are an awesome choice!

So, what’s the verdict? In terms of phytate levels, lectins, and overall nutrition, edible-podded legumes don’t have that much in common with the hard, mature beans that typically come to mind when we hear the word “legume.” And while the small amounts of agglutinins may be a concern for those with autoimmune disease following the autoimmune protocol, the arguments for excluding these foods from a more standard Paleo diet fall short. If we see green beans at the farmers market, are lucky enough to have sugar snap peas growing in the garden, or just want a tasty addition to our veggie menu, edible-podded legumes are an awesome choice!

Citations

“Basic Report: 11300, Peas, edible-podded, raw.” USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. Accessed August 7, 2016.

“Basic Report: 16086, Peas, split, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt.” USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. Accessed August 7, 2016.

Nutrivore Weekly Serving Matrix

An easy-to-use and flexible weekly checklist

to help you maximize nutrient-density.

The Weekly Serving Matrix is very helpful! I’ve been eating along these lines but this really helps me know where to focus vs. which foods serve a more secondary role. It’s super helpful and has taken a lot of worry out of my meal planning. Thanks!

Jan

Dvorak R, et al. “Reduction in the content of antinutritional substances in pea seeds (Pisum sativum L.) by different treatments.” Czech J Anim Sci. 2005;50(11):519-527.

Fairweather-Tait SJ & Wright AJ. “Iron availability from peas (Pisum sativum) and bread containing added pea testa in rats.” Br J Nutr. 1985 Mar;53(2):193-7.

Grant G, et al. “A survey of the nutritional and haemagglutination properties of legume seeds generally available in the UK.” Br J Nutr. 1983 Sep;50(2):207-14.

Mameesh MS & Tomar M. “Phytate content of some popular Kuwaiti Foods.” Cereal Chemistry. 1993;5:502-3.

Osborn TC, et al. “Bean lectins: 5. Quantitative genetic variation in seed lectins of Phaseolus vulgaris L. and its relationship to qualitative lectin variation.” Theor Appl Genet. 1985 Apr;70(1):22-31.

Schlemmer U, et al. “Phytate in foods and significance for humans: food sources, intake, processing, bioavailability, protective role and analysis.” Mol Nutr Food Res. 2009 Sep;53 Suppl 2:S330-75. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900099.

Wang N, et al. “Effect of variety and processing on nutrients and certain anti-nutrients in field peas.” Food Chem. 2008;111(1):132-8.

Weder JK, et al. “Antinutritional factors in anasazi and other pinto beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.).” Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1997;51(2):85-98.

Zdunczyk Z, et al. “Chemical composition and content of antinutritional factors in Polish cultivars of peas.” Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1997;50(1):37-45.